What is Stoicism?

There are countless introductions to Stoicism, but no Stoa is complete without a clear foundation. This guide is meant to serve as a starting point, a shared reference for anyone seeking to understand what Stoicism is, and why it still matters.

Note: This is not a complete guide. I will be updating it frequently, and will also be creating separate guides to expand on some of the concepts below.

Introduction

Stoicism is often described as a philosophy of endurance, discipline, and emotional control, but at its core, it is a practical system for living well in an uncertain world.

Founded in ancient Greece and later refined in Rome, Stoicism asks a simple question: What is actually within your control? More importantly, it forces you to ask yourself how you should live once you understand the answer to that question.

So, what is under your control? According to the Stoics, our impulse, desire, aversion, and our mental faculties in general. Everything else is just noise.

Origins

A shipwreck thousands of years ago led you, the reader, to this very page.

The story goes that Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, was traveling with a cargo of purple dye (a valuable trade good) when his ship wrecked near Athens, where he wandered into a bookseller's shop and began reading about Socrates. Impressed, he asked where he could find someone like that.

At that moment, the Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes happened to walk by. The bookseller pointed and said, "Follow that man."

Zeno became Crates' student.

Crates was a Cynic philosopher. Cynicism is philosophy that strips life down to its bare essentials. The Cynics believed that suffering doesn't come from reality itself, but from desires like wealth, status, and luxury. To live well, they argued, one must live simply, in accordance with nature, and remain indifferent to everything that is not truly necessary.

Crates embodied this philosophy completely. He had given away a vast fortune to live in poverty, wandering Athens in a simple cloak, sleeping wherever he pleased, and speaking bluntly to anyone who would listen.

Under Crates, Zeno learned the foundations of ethical discipline. Having learned endurance, self-control, and freedom from attachment from the Cynics, Zeno wasn't completely comfortable with their extremes; he wanted something more structured. A philosophy that preserved the Cynic ideal of inner freedom, but could exist within normal human society. So, he kept studying, synthesizing the ideas he was learning into something new.

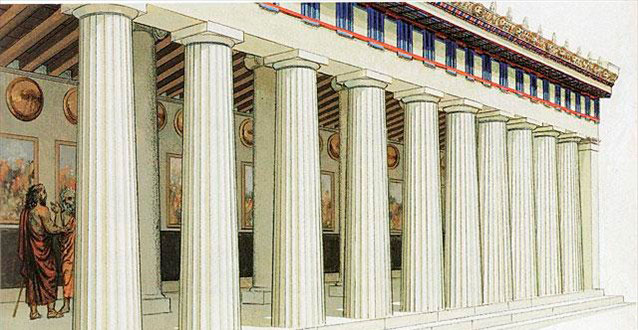

Eventually, Zeno started teaching his own students under a painted colonnade in Athens known as the Stoa Poikile.

Stoa Poikile (Image Source)

From this porch, Stoicism was born.

Key Figures

The names you will frequently encounter in any Stoic community are those of Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, and Seneca. We'll explore these figures below.

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was born Marcus Annius Verus to a wealthy family on April 26, A.D. 121. His parents died when he was young. He was adopted by his grandfather, who passed onto him a happy childhood and provided him with many tutors.

At age 25, Marcus embraced the Stoic way of life completely, devoting himself to studies under Rusticus the Stoic, who introduced him to the writings of Epictetus and taught him to value plain speech, moral discipline, and self-examination.

Not long after, Marcus was adopted by Emperor Antoninus Pius, as part of a carefully planned succession. This placed him on the path to imperial power, though Marcus himself showed little desire for fame or authority. He preferred philosophy, solitude, and study.

In A.D. 161, Marcus became emperor of Rome. His reign was marked not by luxury, but by hardship. Wars on the empire's borders, devastating plague, and constant political pressure. Marcus had 13 children with his wife, but only five daughters and one son survived. Yet throughout these difficulties, Marcus remained committed to Stoic principles, embodying duty, rationality, humility, and acceptance of what lies beyond one's control.

During military campaigns, often writing by lamplight in cold tents, Marcus wrote down a series of personal reflections. These writings later became known as the Meditations, one of the most influential philosophical works in history.

Rather than offering abstract theory, the Meditations reveal a man struggling to live virtuously in an imperfect world. Throughout the meditations, he frequently reminds himself to be patient with others, to act justly, to face death without fear, and to focus only on what he could control: his own character.

Marcus Aurelius remains history's clearest example of a philosopher-king, a man who held absolute power, yet spent his life trying to master himself.

Epictetus

On the other end of the spectrum, we have a man who was born into slavery. Epictetus was born around A.D. 50 in Hierapolis (modern-day Turkey). Despite his status as a slave, Epictetus was allowed to study philosophy under the Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus. At some point in his life, he became permanently lame (according to later accounts, it was the result of being abused by his master). This would later shape his emphasis on inner freedom over external circumstances.

Epictetus was eventually freed. He began teaching philosophy in Rome.

In A.D. 93, Emperor Domitian expelled philosophers from the city, forcing Epictetus into exile, where he settled in Nicopolis, Greece, founding a school that attracted students from across the Roman world.

Unlike other major Stoics, Epictetus wrote nothing himself. His teachings survive through the notes of his student Arrian, who compiled them into the Discourses and the Enchiridion. Epictetus taught that true freedom comes from recognizing the distinction between what is in our control and what is not. A person could be enslaved, poor, ill, or exiled, and still live a good life if they mastered their own mind.

In many ways, Epictetus represents the heart of Stoicism. He shows us that this philosophy is not for elites, but it's a practical system for anyone, in any condition, to live with dignity, resilience, and inner peace.

Seneca

If Epictetus represents Stoicism from the bottom of society, Seneca, like Marcus, represents it from the very top.

Seneca was born around 4 B.C. in Corduba into a wealthy and influential family. He was educated in Rome, where he studied rhetoric and philosophy, quickly gaining a reputation as one of the most brilliant minds of his generation.

Seneca lived at the very center of political power; he became a senator, a celebrated writer, and eventually the tutor and chief advisor to Emperor Nero. For a time, Seneca helped govern the empire, attempting to restrain Nero's impulses through reason and counsel.

The position Seneca found himself in was both a privilege and a trap. Seneca grew enormously wealthy and was often criticized for hypocrisy, how could a Stoic preach simplicity while living in luxury? Seneca was painfully aware of this contradiction, frequently acknowledging his own moral failures and presenting himself not as a perfect sage, but as a man in progress.

As Nero became increasingly unstable and violent, Seneca withdrew from public life. Eventually, he was accused of participating in a conspiracy against the emperor. In A.D. 65, Nero ordered Seneca to take his own life. Seneca faced death calmly, opening his veins and speaking to his friends about philosophy until the end.

His legacy survives in his essays and letters, especially the Letters on Ethics to Lucilius, where he writes honestly about anger, fear, wealth, time, and death. More than any other Stoic, Seneca focuses on the psychological struggles of everyday life.

Seneca shows Stoicism in its most human form. Not the life of a perfect sage, but the life of a flawed person trying, again and again, to live wisely in a world full of temptation, power, and fear.

Central Ideas

The ideas that turn Stoicism into a guide for everyday life.

The Dichotomy of Control

One of the most fundamental principles in Stoic philosophy is the distinction between what is within our control and what is not. This idea is articulated most clearly in the Enchiridion, which opens with this:

We are responsible for some things, while there are others for which we cannot be held responsible.

The things that are under our control, says Epictetus, include our impulse, desire, aversion, and our mental faculties in general. The things which are beyond our control include the body, material possessions, our reputation, status, and anything else that's not directly in our power to control.

The practical implication is not indifference, but clarity. Suffering arises, Epictetus argues, not from events, but from confusing what we can influence with what we cannot. When we attempt to control outcomes, other people, or external circumstances, we place our peace of mind in things that are inheretly unstable.

This offers a shift in focus. Instead of trying to shape the world to our preferences, we shape our character. We cannot guarantee success, approval, or even comfort, but we can always choose how we respond.

Living According to Nature

This phrase is often misunderstood, as if it means to retreat into the wilderness or reject modern life altogther. But fir the Stoics, "nature" did not mean forests and animals; it meant reality itself, the way things actually are. To live according to nature is to live in alignment with reason, rather than our impulses. Humans, the Stoics argued, are rational creatures. Our defining feature is not strength or speed, but our ability to think and reflect.

A good life, therefore, is not one guided by desire, fear, or social pressure, but one guided by clear judgment.

Living according to nature is not passive acceptance, but intelligent cooperation with reality; it is the practice of meeting events without illusion, and then responding with the best version of ourselves that we can.

Providence or Atoms

One of the recurring questions in Stoic thought is whether the universe is guided by providence or governed purely by chance. In other words, does reality unfold according to some rational order, or is it nothing more than a sequence of random events and blind forces?

The Stoics themselves believed in providence. They saw the universe as an interconnected, rational system, governed by logos. Nothing happens in isolation. Every event, no matter how small, is part of a larger causal chain. Stoic practice does not require this belief, however. We catch some agnosticism in the Meditations, for example. Marcus often framed the question this way: either the world is meaningful, or it is accidental.

Either way, your task remains the same; you must use what happens to you as material for character. If the universe is ordered, then everything that happens is necessary; if it is random, then nothing is personal. In both cases, resentment makes absolutely no sense.

All things

Near and far

Are linked to each other

In a hidden way

By an immortal power

So that you cannot pick a flower

without disturbing a star

Virtue Is the Only True Good

Stoicism teaches that the only thing which is truly good is virtue. Everything else (i.e. wealth, health, success, pleasure, reputation) is indifferent. This does not suggest that those things don't have value; it means that they have no moral weight, they can be used well or poorly, but they do not determine whether a person is good or bad. Virtue, for the Stoics, is the quality of one's character. It is expressed through wisdom, justice, courage, and self-discipline.

These virtues offer a practical way of relating to the world. Wisdom brings clear thinking, justice brings acting fairly, courage allows us to face difficulty without collapse, and self-discipline allows us to restrain impulses that undermine long-term well-being. External circumstances can be taken away at any moment. You can lose your job, your health, status, or your possessions, but you cannot lose your capacity to act with integrity unless you choose to do so.

What matters is not what happens, but who you choose to be when it does.

Emotional Mastery, Not Emotional Suppression

A common misconception about Stoicism is that it teaches emotional suppression. The stereotype is of a person who feels nothing, cares about nothing, and endures life in a state of permanent detachment. This is not what the Stoics had in mind. The goal of Stoicism is not to eliminate our emotions, but to understand them. Emotions, in Stoic philosophy, are not random forces that just happen to us, they are the result of our judgments.

For example, fear arises from the belief that something terrible is about to happen; anger arises from the belief that an injustice has been done; envy arises from the belief that someone else possesses something necessary for your happiness. However, if we change the belief, the emotional response changes with it.

Emotional mastery means learning to pause; it means examining the story you are telling yourself before letting it shape your behavior.

The aim is not emotional emptiness; it's emotional clarity.

Acceptance of Fate (Amor Fati)

The phrase Amor Fati wasn't actually used by the Stoics. It was coined by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nonetheless, it indeed embodies Stoicism. Consider the following from the Meditations:

Willingly give yourself up to Clotho, one of the Fates, letting her spin you around however she pleases.

Or,

The proper characteristic of the good man is to love and to greet joyfully all those events which he encounters, and which are linked to him by Destiny.

These passages express a deep form of acceptance for what happens, embracing it as necessary. For the Stoics, every event is part of an unbroken chain of causes; nothing happens in isolation.

To wish that something had not occurred is to wish that the universe were different from what it is, which is futile. To put it into perspective, we can apply it to our own lives by not asking "why did this happen to me", but instead "given that this has happened to me, who can I now choose to be?"

To love your fate is not to celebrate every outcome in our lives, but to refuse to waste energy on resentment. It is a discipline to treat every circumstance, even unwanted ones, as material we can use to strengthen our character.

Final notes

As stated in the introduction, this guide is not fully complete, and will be updated frequently. More guides will come which explore the concepts and characters on a deeper level.

Continue the Discussion

This guide is meant to be reflected on, questioned, and discussed. Create an account or log in to start a discussion about this guide.